Inspired by a recent posting at Nuro where they were looking to build a dynamic GPU VM allocation system, I decided to create a proof-of-concept to get my hands on Kubernetes by writing a custom operator and controller. There are some interesting challenges when it comes to VMs on Kubernetes, and below is the work that I’ve done thus far. It assumes integration into Nuro’s infrastructure based on their ML Scheduler blog post, but could be generalized to any batch job scheduler as well.

At a high level, it creates developer workspaces as pods in Kubernetes, managed by a custom controller, allowing for integration with existing clusters with minimal manual setup, termination, and other lifecycle management. It’s written in Go and deployed on Google Kubernetes Engine.

Pods vs. Actual VMs

The most difficult decision was whether to create actual virtual machines or workspaces as containers on Kubernetes Pods. I eventually chose to use pods for the simplicity, which somewhat defeats the purpose of calling it VMs in the first place, but can still satisfy a user’s requirements for development.

KubeVirt: KubeVirt allows you to run VMs as first-class resources in Kubernetes; however, GKE nodes are themselves VMs. This means KubeVirt requires nested virtualization to run on GKE, which is supported for CPUs but not for GPUs unless the cluster is bare metal. This made the initial idea of managing VMs within Kubernetes seem infeasible. If GPUs can be passed through to a nested VM on GKE, this would drastically simplify the implementation.

GCE VMs: We could provision Google Compute Engine VMs outside of Kubernetes but manage them from the cluster. This gives us real VMs; however, this would mean no integration with existing cluster resources and, more importantly, none of the features of Kubernetes that we want in the first place.

Kubernetes Pod Advantages: By running “VMs” as pods, it makes integration with existing cluster GPUs much easier, allows for native Kubernetes handling, and enables faster starts compared to traditional VMs that can take minutes. We can also easily extend any scheduler to this approach. The tradeoff is that users get a containerized workspace rather than a VM, which could pose issues if they need more privileges, but this made the most sense for a PoC.

Design Goals

Developer Experience: Fast spin-up in <30s with a simple interface for users to access their pod containing all needed tools.

Efficient Lifecycle Management: Idle workspaces should be terminated automatically based on actual GPU utilization, with a 30-minute grace period.

Resource Sharing: Development workspaces should coexist with other jobs on the same cluster, with clear priority rules ensuring jobs aren’t starved.

Scheduler Integration: The system can integrate with an existing scheduler to use the same quota, priority, and preemption rules used for other jobs.

Solution Architecture

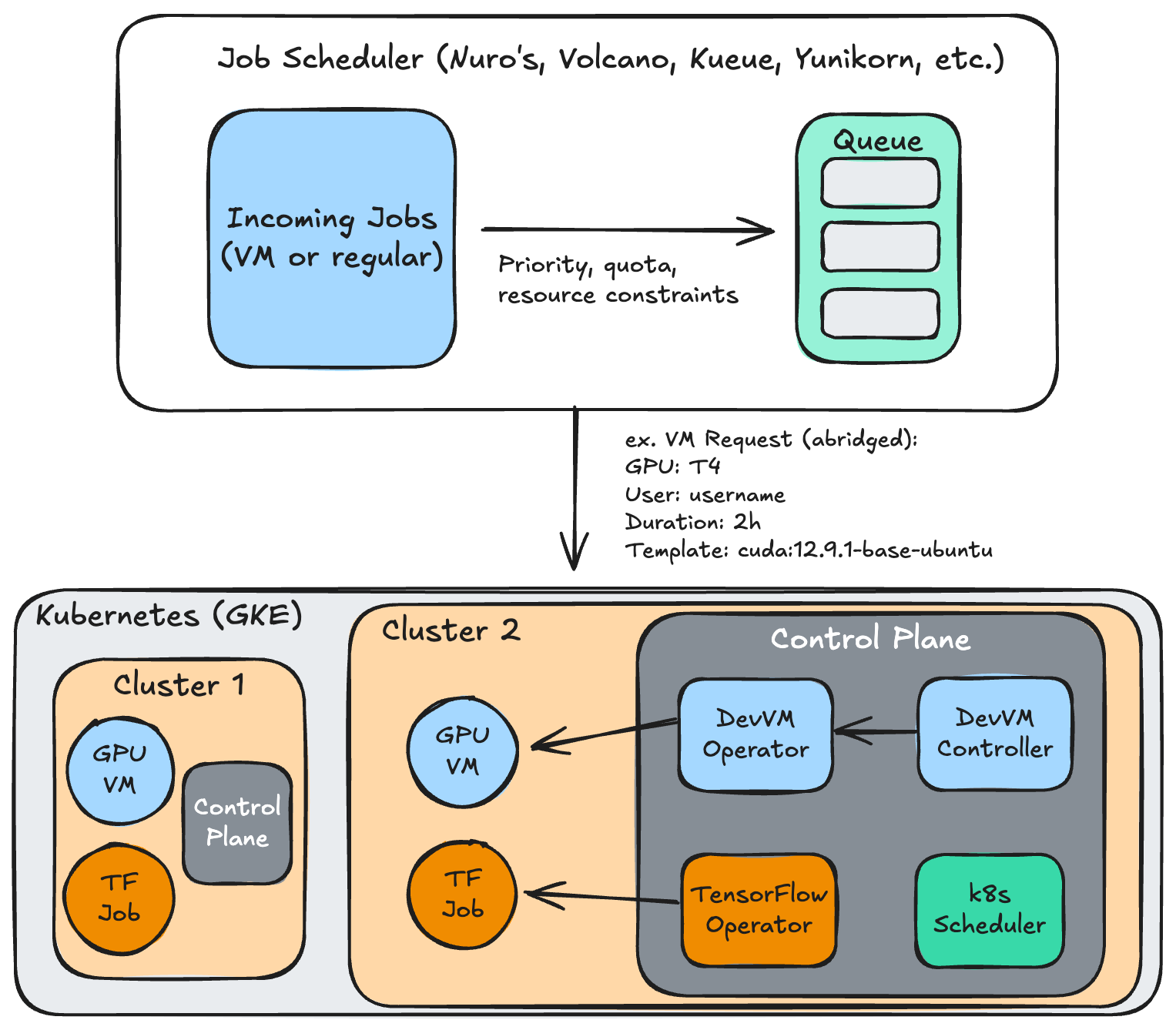

Below is a very simplified architecture diagram: note that each cluster would have its own controller, operator, etc. Training jobs can run alongside the pods as long as enough capacity exists.

Kubernetes Operator: I wrote a custom operator and controller in Go using the controller-runtime framework that watches for workspace requests (a custom resource) and reconciles them into running pods. The operator continuously monitors workspace health, measures GPU utilization, and enforces lifecycle management.

REST API Gateway: A HTTP interface abstracts Kubernetes complexity for external systems to make requests: users can create workspaces by specifying their GPU type, desired lifetime, workspace template, etc.

Job Scheduler Integration: I implemented an adapter that could communicate with Nuro’s existing scheduler to integrate the GPU allocation decisions. In this PoC, I’ve used an in-memory stub but the integration would add the quota, preemptions, and resource allocations previously discussed.

Pod Access: By running NodePorts, we can expose the pod to the user; this is done with a LoadBalancer or Ingress in production, but NodePorts are simpler. The user can access the workspace via SSH, with Jupyter and VSCode Server also being viable options.

Kubernetes CRDs

I defined four Kubernetes CRDs, or custom resource definitions:

DevGPUVMRequest represents a user’s request for a GPU development environment. It includes the username, desired resources (GPU type/count, CPU, memory), maximum lifetime, as well as current lifecycle phase, allocation details, and utilization metrics within the status.

DevGPUVMTemplate provides reusable pod configurations for container image (CUDA, SSH, etc.), mounted volumes, exposed ports, etc.

DevGPUVMLifecyclePolicy defines cluster-level rules for durations, timeout thresholds, preemption, etc.

DevGPUVMQuota can enforce resource limits per namespace or users to fairly share resources.

Lifecycle Management for Efficient Resource Allocation

Idle Detection: Every 60 seconds, the controller executes nvidia-smi inside containers to measure GPU utilization. When utilization drops below 5% for 30 consecutive minutes, the workspace transitions to a “reclaiming” state. This is admittedly a very abstract threshold and should be modified based on users’ expected usage.

GPU Monitoring Choice: I chose nvidia-smi via kubectl exec over NVIDIA DCGM (a tool supported by GKE to export metrics from GPU nodes) because DCGM conflicts with Nsight profiling; an interesting note.

Expiration Enforcement: The controller monitors the deadline from the user’s requested duration, initiating termination as needed. It can also be extended via the API.

Preemption Handling: When a high-priority job, say for training, needs GPU capacity and the cluster is full, the scheduler can signal workspace preemption. The controller can then mark the container, providing a grace period before termination.

Quota Validation: Before creating workspace pods, the controller validates that the request doesn’t exceed team quota limits. If a request exceeds quota, it triggers warnings but doesn’t block allocation as long as GPUs are available, similar to Nuro’s approach.

Integration with a Job Scheduler

Since this was inspired by Nuro’s postings, I built this system around integrating with their scheduler, but any other batch scheduling Kubernetes solution could work.

Allocation Flow: When a workspace is requested, the controller calls the scheduler with the user, desired GPU type/count, and other info. The scheduler would evaluate this against current cluster state, quotas, and priority policies, then return with placements for cluster, accelerator type, capacity, etc.

Placement Guidance: The scheduler can substitute GPU types when preferred accelerators are unavailable (offering an H100 when an A100 was requested, or a T4 as a fallback). It could also direct workspaces to specific clusters across regions based on data locality or cost optimization.

Priority Hierarchy: All development workspaces run at a lower priority than production jobs like training, with priorities coming from the scheduler.

Outcomes

Utilization Improvement: GPU resources are effectively managed through the lifecycle policies, taking advantage of any unused capacity on a shared Kubernetes pool.

Faster Iteration: Users can provision new pre-built workspaces in under 30 seconds (vs. 15-30 minutes for VMs) and easily access them, while also being torn down gracefully.

System Simplicity: True VMs can be more complex to manage; this approach has the k8s benefits while exposing a simple API that can be used with a frontend or cli tool.

Future Additions

Advanced Idle Detection: Enhance idle detection to factor in the type of work users are doing beyond GPU utilization, including SSH connection status, kernel activity, and process monitoring.

Workspace Persistence: Allow users to persist their workspace state and restore it later, perhaps with Google’s Persistent Volumes, or allow migration in case of preemption.

Template Customization: Having a variety of prebuilt templates for users with an UI to add tools of their liking (e.g., PyTorch vs. TensorFlow).

Detailed Metrics: Currently, only basic Prometheus metrics are exposed such as utilization, workspace lifecycle phases, etc. This can be much richer, such as breakdown by user or team, by GPU type, and other low-level metrics.

Reflection

This was my first time writing custom controllers and operators in k8s: I’ve learnt more about the technical details of k8s and containerized GPU workloads, particularly NVIDIA device plugins and GPU drivers in k8s clusters. I also learned about job schedulers and how they drive efficiency (as in Nuro’s use case). Resource management and allocation is a complex but important challenge in infrastructure, and I’ve enjoyed learning more about these topics while implementing a new solution for non-traditional workloads like GPU developer workspaces.

The code for the core of the application can be found here.